Bathing has been an activity that humans have been engaging with for centuries. It can take place in any situation where there is water. It can take place in a bath, shower, river, lake, water hole, pool or the sea, or any other body of water.

The term for the act can vary. It is used in religious practices such as an immersion or baptism. Bathing is used for therapeutic purposes such as water treatments or hydrotherapy and is also associated with recreational water activities such as swimming.

History of Bathing from Wikipedia:

Ancient Greece utilized small bathtubs, wash basins, and foot baths for personal cleanliness. The earliest findings of baths date from the mid-2nd millennium BC. The Greeks established public baths and showers within gymnasiums for relaxation and personal hygiene.

Ancient Rome developed a network of aqueducts to supply water to all large towns and population centres and had indoor plumbing, with pipes that terminated in homes and at public wells and fountains.

The thermae were not class-stratified; being available to all for no charge or a small fee. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the aqueduct system fell into disrepair and disuse. But even before that, during the Christianization of the Empire, changing ideas about public morals led the baths into disfavor.

Japan:

Before the 7th century, the Japanese likely bathed in the many springs in the open, as there is no evidence of closed rooms. In the 6th to 8th centuries the Japanese absorbed the religion of Buddhism from China, which had a strong impact on the culture of the entire country. Buddhist temples traditionally included a bathhouse (yuya) for the monks. Due to the principle of purity espoused by Buddhism these baths were eventually opened to the public. Only the wealthy had private baths.

The first public bathhouse was mentioned in 1266. These were built into natural caves or stone vaults. In iwaburo along the coast, the rocks were heated by burning wood, then sea water was poured over the rocks, producing steam. Because there was no gender distinction, these baths came into disrepute. They were finally abolished in 1870 on hygienic and moral grounds. Author John Gallagher says bathing “was segregated in the 1870s as a concession to outraged Western tourists”.

At the beginning of the Edo period (1603–1868) there were two different types of baths. In Edo, hot-water baths were common, while in Osaka, steam baths were common. At that time shared bathrooms for men and women were the rule. These bathhouses were very popular, especially for men. “Bathing girls” (湯女 yuna) were employed to scrub the guests’ backs and wash their hair, etc. In 1841, the employment of yuna was generally prohibited, as well as mixed bathing. The segregation of the sexes, however, was often ignored by operators of bathhouses, or areas for men and women were separated only by a symbolic line. Today, sento baths have separate rooms for men and women.

Mesoamerica

Spanish chronicles describe the bathing habits of the peoples of Mesoamerica during and after the conquest. Bernal Díaz del Castillo describes Moctezuma as being “…Very neat and cleanly, bathing every day each afternoon…”. Bathing was not restricted to the elite, but was practised by all people.

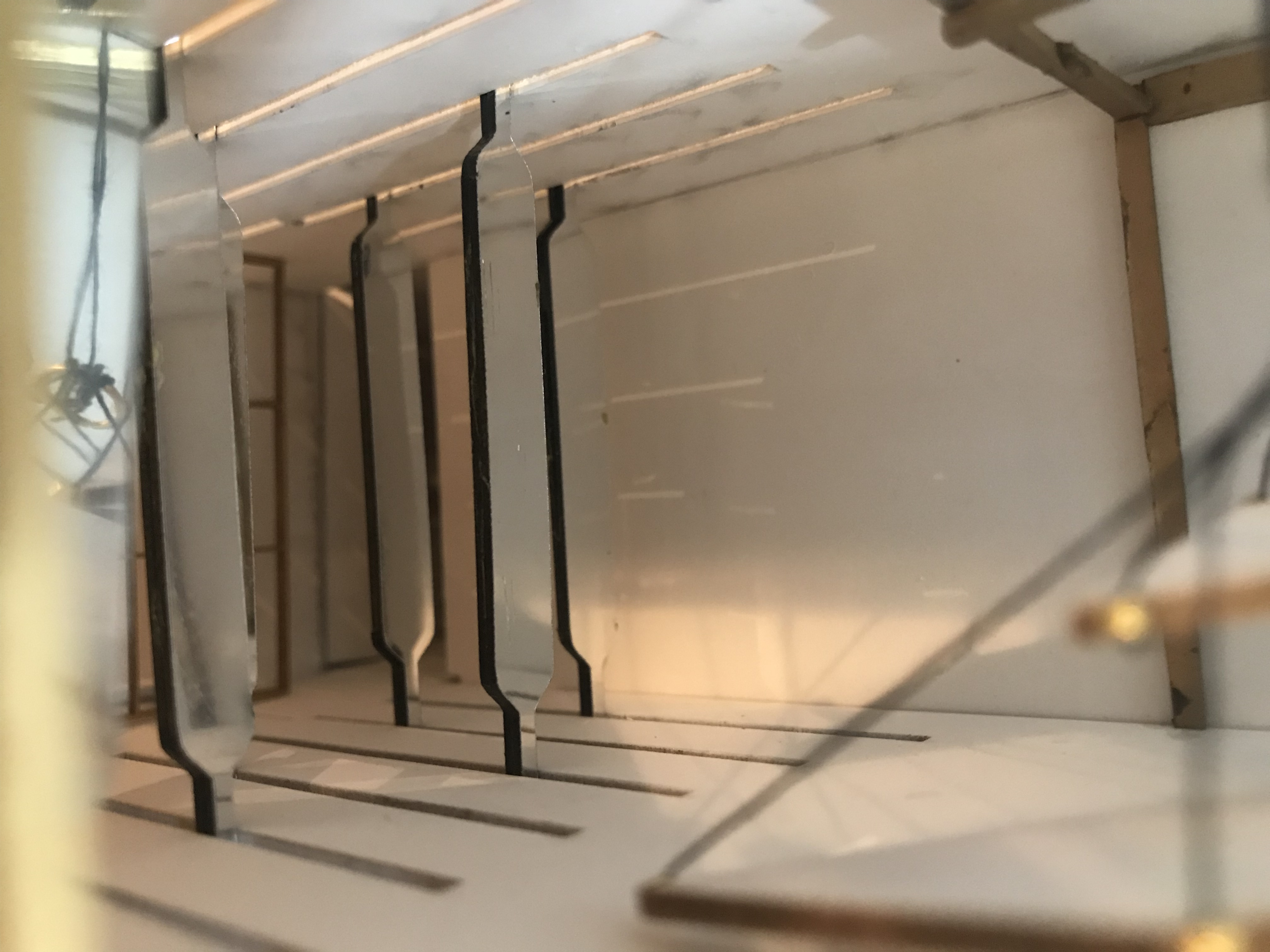

The Mesoamerican bath, consists of a room, often in the form of a small dome, with an exterior firebox known as texictle (teʃict͜ɬe) that heats a small portion of the room’s wall made of volcanic rocks; after this wall has been heated, water is poured on it to produce steam, an action known as tlasas. As the steam accumulates in the upper part of the room a person in charge uses a bough to direct the steam to the bathers who are lying on the ground, with which he later gives them a massage, then the bathers scrub themselves with a small flat river stone and finally the person in charge introduces buckets with water with soap and grass used to rinse. This bath had also ritual importance, and was vinculated to the goddess Toci; it is also therapeutic when medicinal herbs are used in the water for the tlasas. It is still used in Mexico.

Medieval and early-modern Europe

Christianity has always placed a strong emphasis on hygiene. Despite the denunciation of the mixed bathing style of Roman pools by early Christian clergy, as well as the pagan custom of women bathing naked in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing, which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the Church Father, Clement of Alexandria. The Church also built public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near monasteries and pilgrimage sites; also, the popes situated baths within church basilicas and monasteries since the early Middle Ages. Pope Gregory the Great urged his followers on value of bathing as a bodily need.

In the Middle Ages, bathing commonly took place in public bathhouses. Public baths were also havens for prostitution, which created some opposition to them. Rich people bathed at home, most likely in their bedroom, as ‘bath’ rooms were not common. Bathing was done in large, wooden tubs with a linen cloth laid in it to protect the bather from splinters.

Furthermore, from the late Middle Ages through to the end of the 18th century, etiquette and medical manuals advised people to only wash the parts of the body that were visible to the public; for example, the ears, hands, feet, and face and neck. This did away with the public baths and left the cleaning of oneself to the privacy of one’s home. The switch from woolen to linen clothing by the 16th century also accompanied the decline in bathing. Clean linen shirts or blouses allowed people who had not bathed to appear clean and well groomed.

Bathing today:

Public opinion about bathing began to shift in the middle and late 18th century, when writers argued that frequent bathing might lead to better health. Two English works on the medical uses of water were published in the 18th century that inaugurated the new fashion for therapeutic bathing. One of these was by Sir John Floyer, a physician of Lichfiel

The other work was a 1797 publication by Dr James Currie of Liverpool on the use of hot and cold water in the treatment of fever and other illness.

A popular revival followed the application of hydrotherapy around 1829, by Vincenz Priessnitz, a peasant farmer in Gräfenberg. This revival was continued by a Bavarian priest, Sebastian Kneipp (1821–1897), after he read a treatise on the cold water cure. In Wörishofen Kneipp developed the systematic and controlled application of hydrotherapy for the support of medical treatment that was delivered only by doctors at that time.

Captain R. T. Claridge was responsible for introducing and promoting hydropathy in Britain, first in London in 1842, then with lecture tours in Ireland and Scotland in 1843.

Public baths

Large public baths such as those found in the ancient world and the Ottoman Empire were revived during the 19th century. The first modern public baths were opened in Liverpool in 1829. The first known warm fresh-water public wash house was opened in May 1842.

The popularity of wash-houses was spurred by the newspaper interest in Kitty Wilkinson, an Irish immigrant “wife of a labourer” who became known as the Saint of the Slums. In 1832, during a cholera epidemic, Wilkinson took the initiative to offer the use of her house and yard to neighbours to wash their clothes, at a charge of a penny per week, and showed them how to use a chloride of lime (bleach) to get them clean. She was supported by the District Provident Society and William Rathbone. In 1842 Wilkinson was appointed baths superintendent.

In Birmingham, around ten private baths were available in the 1830s. Whilst the dimensions of the baths were small, they provided a range of services. Private baths were advertised as having healing qualities and being able to cure people of diabetes, gout and all skin diseases, amongst others. On 19 November 1844, it was decided that the working class members of society should have the opportunity to access baths, in an attempt to address the health problems of the public.

After a period of campaigning by many committees, the Public Baths and Wash-houses Act received royal assent on 26 August 1846. The Act empowered local authorities across the country to incur expenditure in constructing public swimming baths out of its own funds.

The first London public baths was opened at Goulston Square, Whitechapel, in 1847 with the Prince consort laying the foundation stone.

Hot public baths

Traditional Turkish baths were introduced to Britain by David Urquhart, diplomat and sometime Member of Parliament for Stafford, who for political and personal reasons wished to popularize Turkish culture. He described the system of dry hot-air baths used there and in the Ottoman Empire which had changed little since Roman times. In 1856 Richard Barter read Urquhart’s book and worked with him to construct a bath. They opened the first modern hot water bath at St Ann’s Hydropathic Establishment near Blarney, County Cork, Ireland.

The following year, the first public bath of its type to be built in mainland Britain since Roman times was opened in Manchester, and the idea spread rapidly. It reached London in July 1860, when Roger Evans, a member of one of Urquhart’s Foreign Affairs Committees, opened a Turkish bath at 5 Bell Street, near Marble Arch. During the following 150 years, over 600 Turkish baths opened in Britain, including those built by municipal authorities as part of swimming pool complexes, taking advantage of the fact that water-heating boilers were already on site.

Similar baths opened in other parts of the British Empire. Dr. John Le Gay Brereton opened a Turkish bath in Sydney, Australia in 1859, Canada had one by 1869, and the first in New Zealand was opened in 1874. Urquhart’s influence was also felt outside the Empire when in 1861, Dr Charles H Shepard opened the first Turkish baths in the United States most probably on 3 October 1863.

Cleanliness

By the mid-19th century, the English urbanised middle classes had formed an ideology of cleanliness that ranked alongside typical Victorian concepts, such as Christianity, respectability and social progress. The cleanliness of the individual became associated with his or her moral and social standing within the community and domestic life became increasingly regulated by concerns regarding the presentation of domestic sobriety and cleanliness.

The industry of soapmaking began on a small scale in the 1780s, with the establishment of a soap manufactory at Tipton by James Keir and the marketing of high-quality, transparent soap in 1789 by Andrew Pears of London. It was in the mid-19th century, though, that the large-scale consumption of soap by the middle classes, anxious to prove their social standing, drove forward the mass production and marketing of soap.

Before the late 19th century, water to individual places of residence was rare. Many countries in Europe developed a water collection and distribution network. London water supply infrastructure developed through major 19th-century treatment works built in response to cholera threats, to modern large-scale reservoirs. By the end of the century, private baths with running hot water were increasingly common in affluent homes in America and Britain.

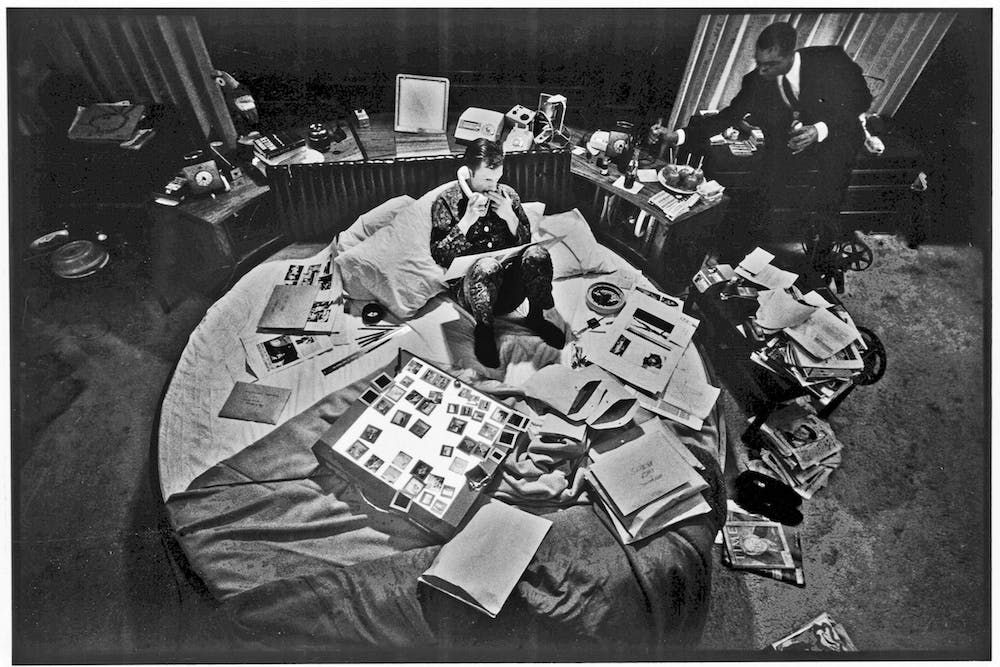

At the beginning of the 20th century, a weekly Saturday night bath had become common custom for most of the population. A half day’s work on Saturday for factory workers allowed them some leisure to prepare for the Sunday day of rest. The half day off allowed time for the considerable labor of drawing, carrying, and heating water, filling the bath and then afterward emptying it. To economize, bath water was shared by all family members. Indoor plumbing became more common in the 20th century and commercial advertising campaigns pushing new bath products began to influence public ideas about cleanliness, promoting the idea of a daily shower or bath.

Ritual Purification:

Ritual purification is the purification ritual prescribed by a religion by which a person is considered to be free of uncleanliness, especially prior to the worship of a deity, and ritual purity is a state of ritual cleanliness.

Bahá’í Faith

In the Bahá’í Faith, ritual ablutions (the washing of the hands and face) should be done before the saying of the obligatory prayers, as well as prior to the recitation of the Greatest Name 95 times. Menstruating women are obliged to pray, but have the (voluntary) alternative of reciting a verse instead; if the latter choice is taken, ablutions are still required before the recital of the special verse. Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith, prescribed the ablutions in his book of laws, the Kitáb-i-Aqdas.

Apart from this, Bahá’u’lláh abolished all forms of ritual impurity of people and things, following Báb who stressed the importance of cleanliness and spiritual purity.

Buddhism

In Japanese Buddhism, a basin called a tsukubai is provided at Buddhist temples for ablutions. It is also used for tea ceremony.

Christianity

The Bible has many rituals of purification relating to menstruation, childbirth, sexual relations, nocturnal emission, unusual bodily fluids, skin disease, death, and animal sacrifices. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church prescribes several kinds of hand washing for example after leaving the latrine, lavatory or bathhouse, or before prayer, or after eating a meal.

Baptism, as a form of ritual purification, occurs in several religions related to Judaism, and most prominently in Christianity; Christianity also has other forms of ritual purification.

Many ancient churches were built with a large fountain in the courtyard. It was the tradition for Christians to wash before entering the church for worship. This usage is also legislated in the Rule of St. Benedict, as a result of which, many medieval monasteries were built with communal lavers for the monks or nuns to wash up before the Daily Office.

The principle of washing the hands before celebrating the holy Liturgy began as a practical precaution of cleanness, which was also interpreted symbolically. “In the third century there are traces of a custom of washing the hands as a preparation for prayer on the part of all Christians; and from the fourth century onwards it appears to have been usual for the ministers at the Communion Service ceremonially to wash their hands before the more solemn part of the service as a symbol of inward purity.”

In Reformed Christianity, ritual purity is achieved though the Confession of Sins, and Assurance of Forgiveness, and Sanctification. Through the power of the Holy Spirit, believers offer their whole being and labor as a ‘living sacrifice’; and cleanliness becomes a way of life (See Romans 12:1, and John 13:5-10 (the Washing of the Feet)).

Hinduism

Various traditions within Hinduism follow different standards of ritual purity and purification; in Smartism, for example, the attitude to ritual purity is similar to that of Karaite Judaism. Within each tradition the more orthodox groups follow stricter rules, but the strictest rules are generally prescribed for brahmins, especially those engaged in the temple worship.

An important part of ritual purification in Hinduism is the bathing of the entire body, particularly in rivers considered holy such as the Ganges; it is considered auspicious to perform this form of purification before any festival, and it is also practiced after the death of someone, in order to maintain purity.

In the ritual known as abhisheka (Sanskrit, “sprinkling; ablution”), the deity’s murti or image is ritually bathed with water, curd, milk, honey, ghee, cane sugar, rosewater, etc. Abhisheka is also a special form of puja prescribed by Agamic injunction. The act is also performed in the inauguration of religious and political monarchs and for other special blessings. Murti of a deity must not be touched without cleansing of hands. One is not supposed to enter a Temple without a bath.

There are various kinds of purificatory rituals associated with death ceremonies. After visiting a house where a death has recently occurred, Hindus are expected to take bath.

Indigenous American religions

In the traditions of many Indigenous peoples of the Americas, one of the forms of ritual purification is the ablutionary use of a sauna, known as a sweatlodge, as preparation for a variety of other ceremonies. The burning of smudge sticks is also believed by some indigenous groups to cleanse an area of any evil presence. Some groups like the southeastern tribe, the Cherokee, practiced and, to a lesser degree, still practice going to water, performed only in bodies of water that move like rivers or streams. Going to water was practiced by some villages daily (around sunrise) while others would go to water primarily for special occasions, including but not limited to naming ceremonies, holidays, and ball games.

Islam

Islamic ritual purification is particularly centred on the preparation for salah, ritual prayer; theoretically ritual purification would remain valid throughout the day, but is treated as invalid on the occurrence of certain acts, flatulence, sleep, contact with the opposite sex (depending on which school of thought), unconsciousness, and the emission of blood, semen, or vomit. Some schools of thought mandate that ritual purity is necessary for holding the Quran.

Ritual purification takes the form of ablution, wudu and ghusl, depending on the circumstance; the greater form is obligatory by a woman after she ceases menstruation, on a corpse that didn’t die during battle and after sexual activity, and is optionally used on other occasions, for example just prior to Friday prayers or entering ihram.

An alternative tayammum (“dry ablution”), involving clean sand or earth, is used if clean water is not available or if an illness would be worsened by the use of water; this form is invalidated in the same circumstances as the other forms, and also whenever water becomes available and safe to use. It is also necessary to be repeated (renewed) before every obligatory prayer.

The fard or “obligatory activities” of the lesser form include beginning with the intention to purify oneself, washing of the face, arms, head, and feet. while some mustahabb “recommended activities” also exist such as basmala recitation, oral hygiene, washing the mouth, nose at the beginning, washing of arms to the elbows and washing of the ears at the end; additionally recitation of the Shahada. The greater form (ghusl) is completed by first performing wudu and then ensuring that the entire body is washed. Some minor details of Islamic ritual purification may vary between different madhhabs “schools of thought”.

Judaism

The Hebrew Bible mentions a number of situations when ritual purification is required, including during menstruation, following childbirth, sexual relations, nocturnal emission, unusual bodily fluids, skin disease, death, and animal sacrifices. The oral law specifies other situations when ritual purification is required, such as after performing excretory functions, meals, and waking. The purification ritual is generally a form of water-based ritual washing in Judaism for removal of any ritual impurity, sometimes requiring just washing of the hands, and at other times requiring full immersion; the oral law requires the use of un-drawn water for any ritual full immersion – either a natural river/stream/spring, or a special bath (a Mikvah) which contains rain-water.

These regulations were variously observed by the ancient Israelites; contemporary Orthodox Jews and (with some modifications and additional leniencies) some Conservative Jews continue to observe the regulations, except for those tied to sacrifice in the Temple in Jerusalem, as the Temple no longer fully exists. These groups continue to observe many of the hand-washing rituals. Of those connected with full ritual immersion, perhaps the quintessential immersion rituals still carried out are those related to nidda, according to which a menstruating woman must avoid physical contact with her husband, especially avoiding sexual contact, and may only resume contact after she has first immersed herself fully in a mikvah of living water seven days after her menstruation has ceased.

Purification was required in the nation of Israel during Biblical times for the ceremonially unclean so that they would not defile God’s tabernacle and put themselves in a position to be cut off from Israel. An Israelite could become unclean by handling a dead body. In this situation, the uncleanliness would last for seven days. Part of the cleansing process would be washing the body and clothes, and the unclean person would need to be sprinkled with the water of purification.

Kalash people

Kalash theology has very strong notions of purity and impurity. Menstruation is confirmation of women’s impurity and when their periods begin they must leave their homes and enter the village menstrual building or “bashaleni”. Only after undergoing a purification ceremony restoring their purity can they return home and rejoin village life. The husband is an active participant in this ritual.